Abstract

This paper discusses characters of leadership in Nepalese politics specifically after the earthquake of 2015.With some examples from the context, it argues that leadership style in Nepal lacks responsible component. Therefore, a culture of responsibility in crafting leadership styles should be promoted in various sectors of the Nepalese community in times to come for a better social order.

Introduction

The earthquake of 7.8 magnitude on April 25, 2015 brought a series of the humanitarian crisis in Nepal. The death and destruction caused by this natural disaster compounded further with the lack of responsible leadership. Such a lack of responsible leadership not only invited foreign “humanitarian” interventions during the rescue operation. It also pushed Nepal towards a sort of humanitarian crisis in the following days when Nepal promulgated a constitution from the Constitution assembly. The constitution disappointed India. In response, India stopped supplies to a landlocked country Nepal.

The protest of a political group against the constitution in the Nepal India border was claimed to be the reason of “supply disruption” by India. The situation is worsening day by day. A recent statement of the United States confirms that due to the shortage of basic necessities, Nepal is gradually entering to the level of the humanitarian crisis. (Statement from the United States Embassy Kathmandu, Nov 5, 2015)

With this background, the following paragraphs are structured to inform: (1) what is responsible leadership? (2) leadership traits in Nepal after the earthquake of 2015, and (3) concluding remarks.

What is responsible leadership?

Like any other leadership style, responsible leadership entails components like care and concern, problem-solving, and facilitation. However, the question embedded with the criterion engages more questions like: to whom to offer care and concern; to whose problem to solve and how; and how to facilitate with what objectives. From this perspective, responsible leadership departs from conventional leadership styles. It not only involves the “other side” but also engages and integrates the adversary into a network of mutual beneficiaries with a scope of dignity and sustainability. Moreover, it aims to engage all those stakeholders who are “less visible” in any other type of leadership.

Creating a value network of multiple stakeholders, (Lord and Brown, 2001), responsible leadership enhances social capital ensuring sustainability and common ground for all those concerned. By so doing, it aims to challenge the social constructs responsible to the making of the conflict in our contemporary world. There is no outsider for responsible leadership. It strives to integrate diversities to make a “rainbow” culture of togetherness and peace.

Responsible leadership is compared with a weaver who makes something more beautiful by weaving different fabrics of the community. Maak (2007) confirms this notion with Plato’s reference as:

Interestingly enough, Plato saw this quite clearly in his ‘‘Statesman,’’ where he noted that people are not sheep, and leaders are not shepherds; Plato regarded the leader as a weaver, whose main task was to weave together different kinds of people into the fabric of society (p. 340).

However, a responsible leader as a weaver attracts questions like weaving from which side? Is this weaver weaving a quilt from outside or weaving a spider’s web from inside? The position of the leader, to a great extent, determines the question: what is responsible leadership? what makes a responsible leader? and how can responsible leadership be developed?

Upanishadic[i] concept Neti Neti refers to the idea that the “truth” is not this and it is not that. Rather, we construct truth according to our requirements and convenience. To learn beyond social construction, one must search for something beyond the realm of the known or something that appears negotiable with the other side. This notion challenges the existing knowledge of the issue in question, and fosters a background to explore the unknown terrain of the knowledge through cooperation and co-creation, that is, to know what you don’t know is the beginning of the knowledge in Plato’s term. In relation to this notion, in responsible leadership, Augsburger identified this idea as the “neither-nor” approach which paves way for the contestants to move beyond their own circumstantial understandings of the issue. Augsburger writes:

In neither-nor cooperation, we move beyond both-end processes of combining perceptions and intended outcomes to co-creation of an alternative solution that neither party has envisioned or engendered. The parties involved neither own the solution nor claim any portion of it as a victory. The outcome is a joint creation–a mutually constructed, equally supported, communally concluded process. (p.53).

Responsible leadership is an attempt to realize sustainable together. It is also a type of transformative leadership in a way that helps shift the paradigm for a better solution for all the stakeholders concerned. When all the stakeholders are addressed, they opt to take ownership of the leadership, and the leader as a person becomes less important. A responsible leader lives in the mind of the people than in the objective reality. In Nepal, a verse from a folk poet attempts to describe responsible leadership as:

K chha jagat ma thulo? : pasina ra bibek

Udesya ke linu?: udi chhunu Chandra ek

Sabai khojchhan sukha, sukha tyo kaha chha?

Afu mitai arulai dinu jaha chha

(What is the greatest thing in the world?: prudence and labor. What should be the goal of a human being ?: strive beyond the sky, there is no goal. Where is eudaimonia?: in embracing the whole cleansing self-interest and ego. My translation).

Leadership after the earthquake in Nepal

Leadership after earthquake exhibited multiple facets. The followings are some of the traits that characterize Nepalese leadership after the earthquake of 2015.

Irresponsible endeavors

Lack of a timely and prompt action to address the chaotic situation after the earthquake was one of the weak factors of Nepalese leadership. The earthquake made about eight million people needing humanitarian assistance in Nepal (Padma, 2015). By that time, Prime Minister of Nepal was in Indonesia, who managed to return three days after the earthquake, only to save himself from aftershocks. Other ministers and political leaders were not visible in public responsibly. It was complete chaos.

To fill the vacuum, the Indian Army landed in Kathmandu airport with a “rescue” mission. Other rescue operations from many countries were on their way to Nepal. Chinese mission was unable to land timely, for Nepalese airports were occupied by the Indian rescue mission. The British rescue mission was not allowed to operate in Nepal by Nepal Army, therefore stationed in India.

Meanwhile, delegates and “well-wishers” from various parts of the world landed in Nepal with materials needed for the victim of the earthquake. Materials they distributed were not only “life-saving” materials, but also “soul-saving” materials like books and pamphlets.

Human trafficking escalated the aftermath of the earthquake (The Guardian, 30 July 2015). The demand of pale-skinned mountain Nepalese girls in the Middle East and the prospect of high supply after the earthquake in Nepal motivated human traffickers. Political, bureaucratic, and security and business leadership of Nepal did not act to stop these malpractices.

Militarism

After the earthquake, the military came to the fore when the political leadership failed to meet public expectations. The military displayed undue power over the civilian government. Rescue operation became solely a military function. Security forces not only attempted to micro-manage the entire relief operation but also tried to influence other constitutional bodies of the Nepal Government. For example, Nepal Army blocked the deployment of British Chinook helicopters which would have been invaluable to the relief effort, only because one of the military personnel, Colonel Kumar Lama, was facing a British trial for his crime against humanity during the Maoist insurgency (1996-2006) in Nepal (BBC, 5 January 2013).

Foreign supports in different forms for the victims of the earthquake was monopolized by the security forces. There was neither transparency nor acceptability. Though, in the later phase, the security gave way to the bureaucracy and political parties in a limited form, that did not stop corruption. Rather, corruption escalated when political stakeholders entered into the scene. Corruption at various levels of political and bureaucratic function forced the Nepalese Prime Minister to acknowledge the situation and promise in public to take action against corruption (Adkin, 2015). Victims lost faith in the system. People started to launch protests against the government (Bhagat, 2015; Buckly and Ramzy, 2015).

Corruption

Centralization of relief material to ensure systematic corruption was practiced after the earthquake. The government failed to tackle (Elliott, 2015). Many other donors opted to fund directly to the victims. (Bell, 2015).

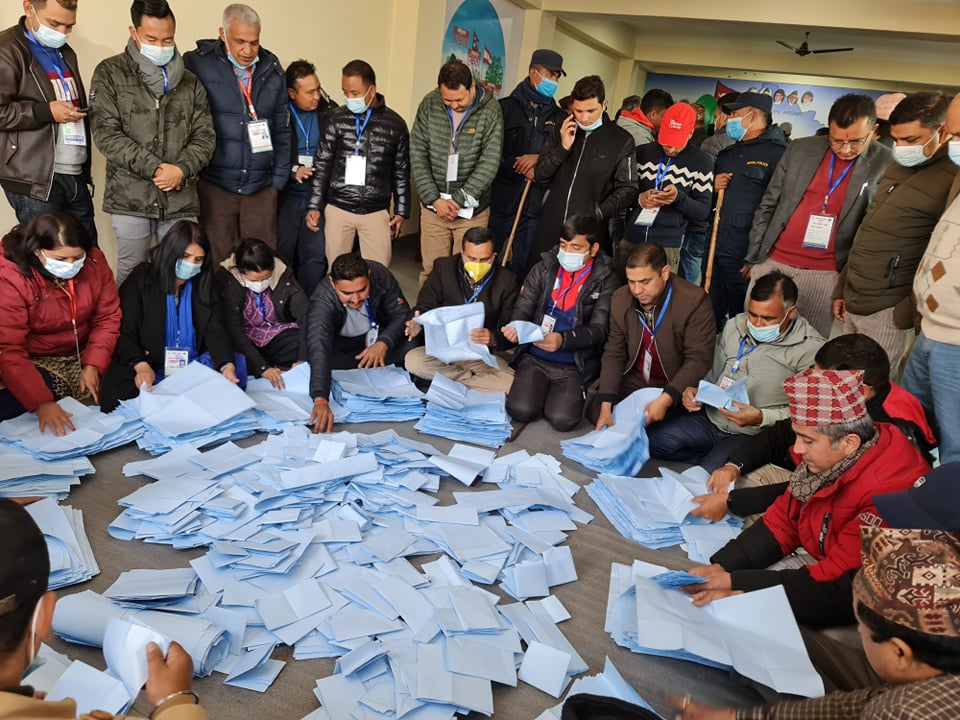

In the beginning, the politicians were not challenged. Officials generally relied on All-Party Mechanisms to take decisions and address conflicts related to relief distribution (The Asian Foundation, June 2015). However, politicians were challenged in the following days when many of them were found to be involved in corruption at various levels of the relief operation (Jha, 16 June 2015).

Impunity

Impunity escalated after the earthquake of 2015. The notion of impunity in the Nepalese political spectrum is as old as its history. Prithvi Narayan Shah, the founder of modern Nepal, justified his crimes and acts of terror as essential acts for the unification of Nepal. When he conquered Kathmandu valley in 1768, he did not bother to investigate crimes made during the time of war either by his own army or by the armies of his opponents. Instead of regulating wars on the principle of justice and fairness, he encouraged the public to employ any means necessary to invade neighboring principalities. Such policies of the state encouraged a culture of impunity that evolved in the following years under various pretexts.

The earthquake was used to serve impunity in Nepal. After the earthquake, when Nepalese military officials suspected of a crime against humanity during the Maoist insurgency were being brought to trails abroad, the military tried to “build up” an image by controlling media and public affairs. To this, a human rights watch group, Amnesty International (2015) warned that “the army’s renewed popularity in the context of earthquake relief should not become an excuse for failing to address past human rights violations and to bring perpetrators to justice (p. 15).

Begging encouraged

At the time of crisis, begging is more effective than in normal periods. In Nepal, begging is a normal practice in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Hindu gods and Buddha himself used to beg for their livelihood. In Hindu tradition, Brahmins are professional beggars. According to Vedic notion, Brahmins are not allowed to take any other profession except studying Veda, performing Vedic rituals and religious ceremonies – karma Kanda, and depend upon the others for food, shelter, and other necessities of life. They are not supposed to work in the field. If they do so, they would be outcasted or degraded from the caste hierarchy. Baun le halo jote jat janchha (a Brahmin becomes outcaste if he ploughs) is a common idiom in Nepal that restrict Brahmins to work in the agriculture field.

Similar restrictions are also culturally sanctioned for the people for the higher castes including Kshetriya and Vaisya. It is also because of the influence of fatalism according to which a fateful person (Bhagyamani) does not need to work because of the good karma of his past life or of his ancestor’s good karma that enables him to appropriate luxury in this life. For this reason, in order to distinguish one superior to the others, Nepalese avoid normal work, particularly manual work in Nepal (Though they accept any kind of work elsewhere). According to Vedic tradition, manual work is assigned to the lower cast, particularly sudra. However, begging is allowed for all castes. It is not something ignoble; rather it is a prestigious profession of the highest caste – brahmins.

The earthquake of 2015 offered an opportunity for political leaders to begin the international arena. Alms or donation or aid was acceptable irrespective of the nature of donors. Many individuals and organizations entered Nepal with various purposes under a banner of “relief aid”. Nepal hosted the International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction-2015 in June to rise aid from the donors. To win the confidence of the donor community, the Nepalese prime Minister publicly vowed that relief aid would reach to the victim (Mathema, 2015). Donor community pledged 4.4 billion US Dollars in aid during the conference. Together with this, a certain surge in remittance inflow (The Kathmandu Post, May 8, 2015) and relief programs of charity, philanthropic, and diaspora organizations inspired political actors to realign political equilibrium to benefit from this opportunity.

Opportunism

Earthquake of 2015 inspired political division (Pokharel and Bhattacharya, 2015). Political parties in the government hastened to the constitution-making process, without testing the assumptions and building consensus with the stakeholders. They not only snuff out the protesting Madheshi[ii] political parties but also irked neighboring country India, without considering the spill-over effect of the conflict in Nepal’s border region. Symptomatically, a group of political dissidents embarked on violence to have their voices heard during the constitution drafting process. As the government failed to address the protest, it finally resulted in Tikapur massacre (Setopati, 2015). Thenceforth, Nepal tried to resolve the issues of discontent through security measures, only to aggravate the situation in the following days.

New constitution triggered political turmoil in Nepal. The internal conflict attained a new dimension when the Constitution of Nepal was not welcomed by India. India suggested for a revision with a view to make it more inclusive and acceptable to the Madheshi minorities, who are fighting for their identity in the southern plain. Whereas China welcomed the move and extended its supports to its northern neighbor (Basnet 2015). The conflict have claimed more than forty human lives, including security persons, children, women and a foreigner (Indian).

Conclusion

Irresponsible leadership of the political parties after the earthquake raised questions about their legitimacy in the public. It further feared them of a sort of “palace revolution” which would overthrow the ruling parties. When they found India against them, they attempted to invite turmoil, engaging other regional and international players, not only to save their political supremacy but also to engage people in an abstract sense of identity instilled with nationalistic aroma.

To aggravate the situation further, Nepal has tried to internationalize the issue that might demand humanitarian and diplomatic intervention (The Tribune, 2015). But, intervention in a hot spot surrounded by three nuclear powers, China, Pakistan, and India, might escalate the conflict to a new dimension than bringing the conflicts to a negotiation table. The role of India in Nepalese movements, specifically in the Maoists insurgency that brought Maoist to power is significant (Lawoti, 2010). Its role has further been strengthened by Nepal’s geophysical configuration and cultural factors. Making a neighbor an enemy is like sleeping with a snake. Therefore, India must be persuaded that the ongoing unofficial blockade will complicate the life of the common people not that of the political elites. To restore friendliness and harmony, some other options must be tried for mutual benefit.

Finally, without restoring an ethos of social responsibility, there can be no meaningful and sustained economic recovery (Sachs, 2011). Responsibility is missing from Nepalese leadership traits. Nepal has observed many leadership styles like charismatic, authentic, transformational, spiritual, or ethical. But, responsible leadership in various sectors of the community is yet to develop.

References

Augsburger, D. W. (1992). Conflict Mediation Across Cultures: Pathways and Patterns. Kentucky: John Knox Press.

BBC. (5 January 2013). Nepal’s Colonel Kumar Lama charged in the UK with torture. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-20914282

Lord, R. G. and Brown, D. J. (2001). Leadership, Values, and Subordinate Self-Concepts. The Leadership Quarterly 12, 133–152.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics. 74:329–343. DOI 10.1007/s10551-007-9510-5.

Padma, T.V. (2015.) Himalayas could be hit by more powerful quakes in coming decades, warn scientists. The Third Pole. April 30, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.thethirdpole.net/himalayas-could-behit-by-more-powerful-quakes-soon-warn-scientists/

Statement from the United States Embassy Kathmandu. (November 5, 2015). Retrieved from http://nepal.usembassy.gov/pr-2015-11-05.html

The Guardian (30 July, 2015). Indian gangs found trafficking women from earthquake-hit Nepal. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/law/2015/jul/30/indian-gangs-trafficking-women-nepal-earthquake

Adkin, R. (06/26/2015). Nepal Prime Minister vows to fight corruption in doling out earthquake aid. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/26/quake-hit-nepal-faces-scr_n_7670750.html

Bhagat, P. (04/30/2015). An Earthquake Exposes Nepal’s Political Rot. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/30/an-earthquake-exposes-nepals-political-rot/

Buckley, C., and Ramzy, A. (04/28/2015). Frustration grows in Nepal as earthquake reliefs trickles in. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/29/world/asia/nepal-katmandu-earthquake-relief.html?_r=0

Elliott, J. (04/27/2015). Nepal Earthquake Deaths: Blame Weak, Corrupt Politicians. Newsweek. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/nepal-earthquake-deaths-blame-weak-corrupt-politicians-325530

Thomas Bell, (25 May, 2015). One month on, red tape hampers Nepal aid. Aljazeera, retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2015/05/nepal-aid-earthquake-corruption-150524135716175.html

The Asian Foundation, UK Aid and Democracy Resource Center. (June, 2015). Aid and Recovery in Post-Earthquake Nepal. San Francisco, CA: The Asia Foundation). Retrieved from http://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/AWAidandRecoveryQualitativeFieldMonitoring.pdf

Jha, D. (June 16, 2015). Putting the last first. The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved from http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/printedition/news/2015-06-15/putting-the-last-first.html

Amnesty International. (2015). Nepal Earthquake recovery must safeguard Human Rights. Retrieved from https://www.amnestyusa.org/sites/default/files/p4583_report_-_nepal_report_on_earthquake_web.pdf_-_adobe_acrobat_pro_0.pdf

The Kathmandu Post. (May 8, 2015). Remittance inflow up post-earthquake. Retrieved from http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2015-05-08/remittance-inflow-up-post-earthquake.html

Mathema, P. (2015) Nepal PM appeals for quake aid, vows funds will reach victims. Reliefweb. (June 25, 2015). Retrieved from http://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/nepal-pm-appeals-quake-aid-vows-funds-will-reach-victims

Basnet, P.B. Nepal’s Himalayan leap. India Today. October 5, 2015. Retrieved from http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/nepals-himalayan-leap/1/481263.html

Seopati. (2015). 7 police personnel, one child killed in Tikapur: Kailali District Administration Office. Setopati. (August 24, 2015). Retrieved from http://m.setopati.net/news/8784/

Pokharel, K. and Bhattacharya, S. (29 April, 2015). Aftermath of Nepal Earthquake Widens the Country’s Political Divisions. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/aftermath-of-nepal-earthquake-widens-the-countrys-political-divisions-1430320936

The Tribune. October 3, 2015. Nepal raises India’s ‘trade blockade’ at UN. Retrieved from http://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/nepal-raises-india-s-trade-blockade-at-un/141315.html

Sachs, J. (201 1). The price of civilization: Economics and ethics after the fall. London: The Bodley Head.

Lawoti, M. (2010). Evolution and growth of the Maoist insurgency. In The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century. eds. Mahendra Lawoti and Anup K. Pahari. Routledge: New Delhi.

[i] Upanishad is an ancient scripture of Vedic tradition, Neti Neti means neither this nor that.

[ii] Madheshi parties represent political groups of the communities along Nepal India border in the south. They claim to be marginalized systematically from Nepal state. Their demands include fair representation of Madhesi group in state administration and security according to the population, and granting rights to language and cultural practices in federal states in Nepal. They have been trying to voice their concerns through various methods, including mass strike, constitution boycott. However, their protest has become violent after the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal in September 20, 2015.